Sahel

- See also Sahel, Tunisia, a region of eastern Tunisia, Sahel Region, a region of Burkina Faso, and Sahel (Eritrea), a former province of Eritrea.

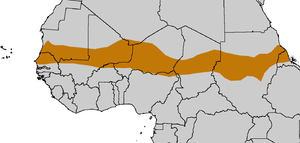

The Sahel is the ecoclimatic and biogeographic zone of transition between the Sahara desert in the North and the Sudanian savannas in the south. It stretches across the north of the African continent between the Atlantic Ocean and the Red Sea. The Sahel covers parts of the countries of Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Algeria, Niger, Nigeria, Chad, Sudan, Somalia, Ethiopia and Eritrea.

Contents |

Geography

The Sahel runs 3862 km (2,400 miles) from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east, in a belt that varies from several hundred to a thousand kilometers (620 miles) in width, covering an area of 3,053,200 square kilometers (1,178,800 square miles). It is a transitional ecoregion of semi-arid grasslands, savannas, steppes, and thorn shrublands lying between the wooded Sudanian savanna to the south and the Sahara to the north.[1]

The topography of the Sahel is mainly flat, and the region mostly lies between 200 and 400 meters elevation. Several isolated plateaus and mountain ranges rise from the Sahel, but are designated as separate ecoregions because their flora and fauna are distinct from the surrounding lowlands. Annual rainfall varies from around 200 mm in the north of the Sahel to around 600 mm in the south.[1]

Over the history of Africa the region has been home to some of the most advanced kingdoms benefiting from trade across the desert. Collectively these states are known as the Sahelian kingdoms.

Flora and fauna

The Sahel is mostly covered in grassland and savanna, with areas of woodland and shrubland. Grass cover is fairly continuous across the region, dominated by annual grass species such as Cenchrus biflorus, Schoenefeldia gracilis, and Aristida stipoides. Species of Acacia are the dominant trees, with Acacia tortilis the most common, along with Acacia senegal and Acacia laeta. Other tree species include Commiphora africana, Balanites aegyptiaca, Faidherbia albida, and Boscia senegalensis. In the northern part of the Sahel, areas of desert shrub, including Panicum turgidum and Aristida sieberana, alternate with areas of grassland and savanna. During the long dry season, many trees lose their leaves, and the predominantly annual grasses die.

The Sahel was formerly home to large populations of grazing mammals, including the Scimitar-horned Oryx (Oryx dammah), Dama Gazelle (Gazella dama), Dorcas Gazelle (Gazella dorcas) and Red-fronted Gazelle (Gazella rufifrons), and Bubal Hartebeest (Alcelaphus busephalus buselaphus), along with large predators like the African Wild Dog (Lycaon pictus), Cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus), and Lion (Panthera leo). The larger species have been greatly reduced in number by over-hunting and competition with livestock, and several species are vulnerable (Dorcas Gazelle and Red-fronted Gazelle), endangered (Dama Gazelle, African Wild Dog, cheetah, lion), or extinct (the Scimitar-horned Oryx is probably extinct in the wild, and the Bubal Hartebeest is extinct).

The seasonal wetlands of the Sahel are important for migratory birds moving within Africa and on the African-Eurasian flyways.[1]

Early agriculture

The first instances of domestication of plants for agricultural purposes in Africa occurred in the Sahel region circa 5000 BCE, when sorghum and African Rice (Oryza glaberrima) began to be cultivated. Around this time, and in the same region, the small Guineafowl were domesticated.

Around 4000 BCE the climate of the Sahara and the Sahel started to become drier at an exceedingly fast pace. This climate change caused lakes and rivers to shrink rather significantly and caused increasing desertification. This, in turn, decreased the amount of land conducive to settlements and helped to cause migrations of farming communities to the more humid climate of West Africa.[2]

Transhumance

Traditionally, most of the people in the Sahel have been semi-nomads, farming and raising livestock in a system of transhumance, which is probably the most sustainable way of utilizing the Sahel. The difference between the dry north with higher levels of soil-nutrients and the wetter south is utilized so that the herds graze on high quality feed in the North during the wet season, and trek several hundred kilometers down to the south, to graze on more abundant, but less nutritious feed during the dry period. Increased permanent settlement and pastoralism in fertile areas has been the source of conflicts with traditional nomadic herders.

Sahelian kingdoms

The Sahelian kingdoms were a series of empires, based in the Sahel, which had many similarities. The wealth of the states came from controlling the Trans-Saharan trade routes across the desert. Their power came from having large pack animals like camels and horses that were fast enough to keep a large empire under central control and were also useful in battle. All of these empires were also quite decentralized with member cities having a great deal of autonomy. The first large Sahelian kingdoms emerged after 750, and supported several large trading cities in the Niger Bend region, including Timbuktu, Gao, and Djenné.

The Sahel states were limited from expanding south into the forest zone of the Ashanti and Yoruba as mounted warriors were all but useless in the forests and the horses and camels could not survive the heat and diseases of the region.

20th-century droughts

There was a major drought in the Sahel in 1914, caused by annual rains far below average, that caused a large-scale famine. The 1960's saw a large increase in rainfall in the region, making the Northern drier region more accessible. There was a push, supported by governments, for people to move northwards, and as the long drought-period from 1968 through 1974 began, the grazing quickly became unsustainable, and large-scale denuding of the terrain followed. Like the drought in 1914, this led to a large-scale famine, but this time it was somewhat tempered by international visibility and an outpouring of aid. This catastrophe led to the founding of the International Fund for Agricultural Development.

In June to August, 2010, famin struk. Dehydration killed and 1 person in Niger, while others in the region were at risk of water shortages on June 1st.[3].

A new heatwave hit Niger on June 21, causing a increased area of drought. Niger's crops to failed and famine to occer. 350,000 faced starvation and 1,200,000 were at risk of famine.[4].

In over-heated Chad, the temperature reached 47.6°C (117.7°F) on June 22 in Faya, breaking a record set in 1961 at the same location. Niger tied its highest temperature record set in 1998, on also June 22, at 47.1°C in Bilma. That record was broken the next day, on June 23 when Bilma hit 48.2°C (118.8°F). The hottest temperature recorded in Sudan was reached on June 25, at 49.6°C (121.3°F) in Dongola, breaking a record set in 1987.[5]

3 years of famine and the resent sand storms devastates Niger on July 14th. diarrhea, starvation, gastroenteritis, malnutrition and respiratory diseases kill and sicken may children. The new military junta is appealing for international food aid and has taken serious steps to calling over seas help since coming to office in February 2010.[6].

On July 26 the heat reached near record levels over Chad and Niger[7].

About 20 had died in northern Niger of dehydration on July the 27th.

Desertification and soil loss

Both over farming, over grazing, over population of marginal lands and natural soil erosion are causing serious desertification of the region.[8][9]

Major dust storms are a frequent occurrence as well. During the November of 2004 a number of major dust storms hit the Chad, Nigeria and northern Cameroon originating in the Bodélé Depression.[10] This is a common area for dust storms (occurring, on average, 100 days every year).

On the 25 August, 2008, heavy dust storms went over the eastern plains of Somalia and the northeast of a still drought hit Kenya.[11] On March the 23rd, 2010 a major sandstorms hit both Mauritania, Senegal, the Gambia, Guinea Bissau, Guinea and inland Sierra Leone. Another got southern Algeria, inland Mauritania, Mali and northern Côte d’Ivoire[12] at the same time.

See also

- Community of Sahel-Saharan States

- Epidemiology

- Green Sahara

- Pan Sahel Initiative

- Sahara Conservation Fund

- Trans-Sahelian Highway

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Magin, Chris (2001). "Sahelian Acacia savanna". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. http://www.worldwildlife.org/wildworld/profiles/terrestrial/at/at0713_full.html. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ↑ O'Brien, Patrick K., ed (2005). Oxford Atlas of World History. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 22–23.

- ↑ "Drought threatens African humanitarian crisis - Channel 4 News". Channel4.com. 2010-07-01. http://www.channel4.com/news/articles/world/africa/drought+threatens+african+humanitarian+crisis/3697427. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Masters, Jeff. "NOAA: June 2010 the globe's 4th consecutive warmest month on record". Weather Underground. Jeff Masters' WunderBlog. http://www.wunderground.com/blog/JeffMasters/comment.html?entrynum=1544. Retrieved 21 July 2010.

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ "Wunder Blog : Weather Underground". Wunderground.com. http://www.wunderground.com/blog/JeffMasters/comment.html?entrynum=1516. Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- ↑ Tripod.com

- ↑ NASA.gov

- ↑ "Dust Storm in the Bodele Depression". Nasa. http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/NaturalHazards/view.php?id=14230. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ↑ Eoearth.org

- ↑ Eosnap.com

- Azam (ed.), Conflict and Growth in Africa: The Sahel, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (1999), ISBN 92-64-17101-0.